You can hear perfectly well.

Yet somehow, nothing makes sense.

Words arrive like badly tuned radio signals, half formed and oddly timed.

You nod.

You smile.

You say “sorry, what?” for the third time in one minute.

Eventually, people stop repeating themselves.

Eventually, they think you are rude.

Or slow.

Or not paying attention.

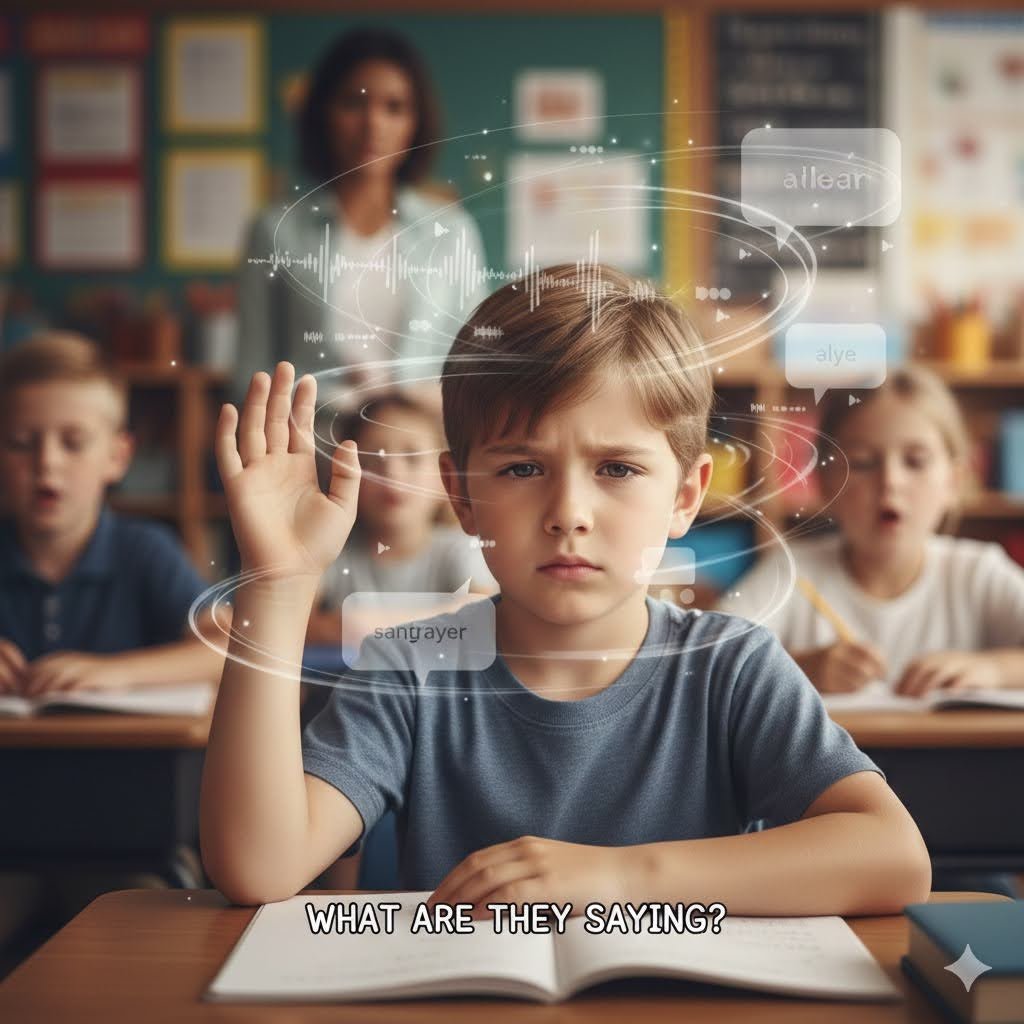

This all began for me when my eight year old daughter said, very calmly, “Mummy, I can hear people but I don’t always know what they’re saying,” and suddenly the whole thing felt less theoretical and far more urgent.

Welcome to the strange world of Auditory Processing Disorder.

What Is Auditory Processing Disorder?

Auditory Processing Disorder, often shortened to APD, is not a hearing problem.

The ears work.

The brain does not.

More precisely, the brain struggles to interpret the sounds the ears collect.

Speech reaches the ear normally, yet the message arrives scrambled once it hits the brain.

Think of it like subtitles that lag behind the film.

The sound is there.

The timing is wrong.

And the plot becomes wildly confusing.

People with APD often hear sounds clearly, yet cannot separate speech from background noise.

They may struggle with fast talkers, unfamiliar accents, group conversations or echoey rooms.

You may be surprised to know that APD is sometimes called “hidden hearing loss” because standard hearing tests almost always come back normal.

Which is deeply unhelpful.

It is a bit like taking your car to the garage because it will not start, only to be told the wheels look fine.

What Does APD Actually Feel Like?

This is where it gets interesting.

And frustrating.

And rather misunderstood.

People with APD often describe speech as muffled, distorted or incomplete.

Not quiet.

Just unclear.

Imagine trying to follow a conversation through a badly tuned walkie talkie while standing next to a blender.

That is about right.

Common experiences include:

• Frequently saying “huh?” or “what?”

• Mishearing similar sounding words

• Struggling to follow instructions with several steps

• Losing track of conversations in noisy places

• Taking longer to respond to questions

• Feeling mentally exhausted after listening

Here is something most people never realise.

Research shows that people with APD use significantly more brain energy just to decode speech than neurotypical listeners.

Listening, for them, is not passive.

It is cardio.

Who Does APD Affect?

APD can affect children and adults.

However, it is most often identified in school-age children.

That makes sense.

Classrooms are noisy.

Teachers talk quickly.

Instructions come in bursts.

And background chatter never truly stops.

APD is more common in:

• Children with ADHD

• Autistic children

• Children with dyslexia or language disorders

• Children born prematurely

• Children with frequent ear infections in early life

When your own child starts coming home from school convinced her friends are annoyed with her for not responding properly, those statistics stop being numbers and start being very personal.

What tends to surprise parents is this.

Around two thirds of children diagnosed with APD also meet criteria for another neurodevelopmental condition.

Which explains why it so often hides in plain sight.

It borrows the coat of ADHD.

It borrows the hat of dyslexia.

And it slips quietly through the diagnostic cracks.

Does APD Start in Childhood Or Appear Later?

Both.

And this is where things get complicated.

Most cases begin in childhood, often linked to early ear infections, delayed language development or neurodevelopmental differences.

However, APD can also develop later in life.

Adult onset APD may appear after:

• Head injury

• Stroke

• Long-term noise exposure

• Neurological illness

• Age-related changes in brain processing

Here is a fact nobody warns you about.

Some researchers believe that hormone changes around menopause may subtly affect auditory processing in certain women.

Yet another unexpected souvenir from midlife.

Suddenly the television sounds mumbled.

Meetings feel exhausting.

And you start blaming everyone else’s diction.

Why Is APD So Often Missed?

Because it looks like something else.

A lot like something else.

Children with APD are frequently labelled as:

• Not paying attention

• Daydreaming

• Disruptive

• Slow learners

• Anxious

• Rude

Adults are often told they have:

• Anxiety

• Social problems

• Poor concentration

• Hearing loss

Here is the part that borders on tragic.

Many children with APD are first referred for behavioural problems rather than listening difficulties.

Which rather misses the point.

The child is not ignoring you.

Their brain simply did not catch the sentence in time.

It is not defiance.

It is delayed delivery.

How Is APD Diagnosed?

Carefully.

And usually late.

APD cannot be diagnosed through standard hearing tests.

Those only measure whether sound reaches the ear.

Instead, assessment is done by specialist audiologists using complex listening tasks.

These may test:

• Understanding speech in background noise

• Recognising rapid speech

• Remembering spoken sequences

• Distinguishing similar sounds

One important detail most families do not hear soon enough.

Most clinics will not test for APD before the age of seven.

The auditory system is still developing before then.

Another awkward truth.

In the UK, access to APD assessment varies wildly by region, and many families end up going private.

Which is both inconvenient and financially character building.

Can APD Improve Over Time?

Sometimes.

Sometimes not.

Children’s brains are highly plastic, which means skills can improve with the right support.

However, APD does not usually vanish politely.

Instead, many people develop coping strategies.

Adults often say things like:

“I always sit on the left side in meetings.”

“I watch people’s lips without realising.”

“I avoid noisy restaurants unless the food is exceptional.”

Here is something genuinely hopeful.

Auditory training programmes can physically strengthen neural timing pathways in the brain over several months.

The brain can be trained.

It just needs repetition, patience and rather a lot of headphones.

How Is APD Treated Or Managed?

There is no pill for APD.

Which is both disappointing and entirely predictable.

Management usually involves three approaches.

First, environmental changes.

• Sitting near the speaker

• Reducing background noise

• Using carpets and soft furnishings

• Wearing classroom microphones

Second, auditory training.

These are structured listening exercises designed to improve sound processing speed and accuracy.

Third, coping strategies.

• Breaking instructions into steps

• Asking for repetition without shame

• Using visual supports

• Recording important information

A quietly impressive detail.

Classroom FM systems can improve speech understanding by up to half for children with APD.

Which is proof that sometimes technology actually does what it promises.

The Emotional Side Nobody Talks About

This matters.

A lot.

Children with APD often feel:

• Embarrassed

• Anxious

• Stupid

• Isolated

They may withdraw socially because conversation feels too hard.

Adults may avoid meetings, parties and phone calls.

Not because they dislike people.

Because people sound like static.

Another uncomfortable truth.

Studies show higher rates of social anxiety in people with untreated APD.

Not because they are naturally anxious.

Because being misunderstood hurts.

And being blamed hurts more.

Why This Matters More Than We Think

Here is the part that stopped me in my tracks.

As someone who has learned, slowly and rather painfully, that not all listening problems are about attention, watching my own daughter struggle to explain that she could hear but not always understand has taught me more about listening than any textbook ever could.

A child saying “I can hear but I can’t understand” is not being dramatic.

They are being precise.

And precision deserves investigation.

Final Thoughts

Auditory Processing Disorder sits in an awkward gap between hearing and thinking.

Too medical for teachers.

Too invisible for doctors.

Too subtle for quick answers.

Yet for the people living with it, every conversation is a small decoding puzzle.

So perhaps the next time someone says “sorry, what?” for the third time, we pause before we sigh.

Listening is not always simple.

Sometimes, the sound arrives.

The meaning just takes the scenic route

Have you ever wondered whether someone in your life hears perfectly well, yet struggles to understand what is being said?